Michael Patterson is, if nothing else, adept at promoting himself and his plans for developing 113 acres of wooded land he owns in southern Maine. He has a blog and a robust YouTube presence, much of it devoted to selling real estate. He graced the cover of the November issue of Woodall’s Campground Magazine, a puppy licking his face, in a photo taken at a camping industry convention. He has been widely quoted in local news stories, explaining his love of nature and his desire to be a good neighbor.

“I don’t want to damage the environment,” he’s quoted in a Portsmouth Herald story a couple of days ago. “If I damage it, then it destroys what I’m trying to create because I’m trying to keep it wilderness.”

If that sounds a bit defensive, it’s because Patterson’s plans are rubbing some of his neighbors the wrong way. And if it sounds a bit hyperbolic, that’s because only a real estate developer would describe this chunk of Maine as “wilderness.” But it’s all of a piece with his desire to build a 44-site “very woodsy” and “high-end” glampground directly across a 30-acre pond from another even larger glampground, because nothing says “minimal environmental impact” quite like 22 or more RV pads, as many as 22 guest cottages, new roads, a couple of turnaround-loops for firetrucks and RVs, three laundry/bathhouse facilities and, eventually, a swimming pool. Because who wants to go swimming in a spring-fed pond?

This being winter in Maine, a lot of local residents have decamped for warmer climes, but enough have stuck around—or are keeping up with local events from afar—for a petition opposing Patterson’s plans to gather more than a thousand signatures. Started by local resident Brian Dumont and addressed to a Sanford building and permit safety specialist, the petition stresses the adverse environmental impact a new glampground would have on the area and cites a need to “protect our natural spaces . . . not just for their inherent beauty but also for their ecological importance.”

Unfortunately, the petition inadvertently also makes the case that this is one barn from which the horse has already bolted. “The vibrant wildlife ecosystem that once thrived here has been dramatically reduced due to over-camping along its shores,” the petition observes. “A few years ago, there were an abundance of native turtles, birds of many types and native fish species including horn pout, pickerel, perch and sunfish. Today almost none of these remain.”

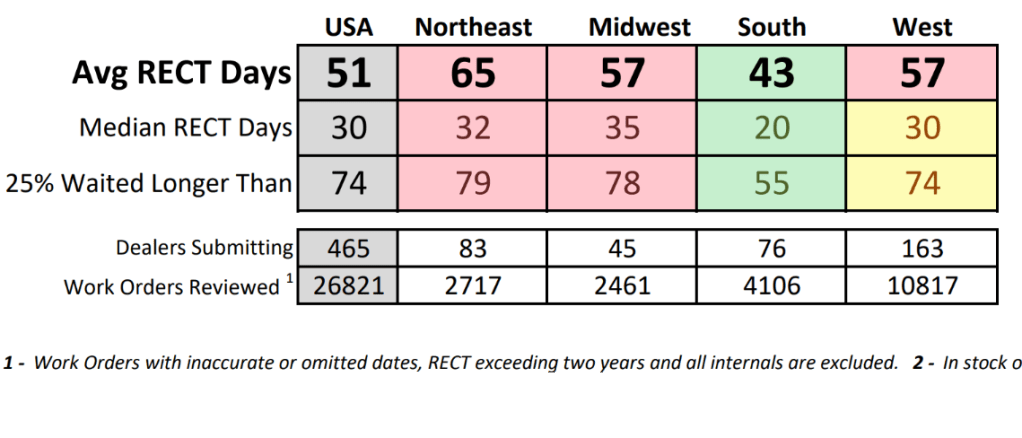

Looking at the map above, it’s hard to see how it could be otherwise. The red borders of individual building lots indicate that virtually all of the land around the pond has been developed; Patterson’s glampground would be limited to just three fingers extending to the shore. The large blank area on the left side of Sand Pond and above Mud Pond, meanwhile, is occupied by Huttopia Southern Maine, one of a handful of U.S. glampgrounds owned by a French-based company that has approximately 60 more such resorts in Europe. This particular establishment has more than 80 luxury tents on platforms, most with en suite bathrooms, as well as half-a-dozen “tiny house” cabins, a pool, playground, restaurant, bar and lounge, store—everything one might need to survive in the wilderness.

There are times when it seems even Patterson must know the absurdity of his pretensions. One of his blog/YouTube segments, for example, describes his use of a Bobcat T770 to clear approximately 60 acres of forest floor, ostensibly as a fire prevention measure. But it also “enhanced the land’s aesthetics” by promoting “the growth of new branches on existing trees, offering more privacy for future campsites,” so it’s your guess what’s really the primary motivation here or how much bigger this project will become . Meanwhile, even as he acknowledged to the Portsmouth Herald that “not everyone enjoys the summertime sounds and autumn activities that can be heard across the water at Huttopia,” Patterson rather likes the festive feel of it all.

“I saw their tiki lights hanging from their campers across the pond, ” he said, referring to the campground that predated Huttopia’s arrival in 2019. “They’d have karaoke, and I could hear the awful singing. I thought it was awesome.”

How all this will play out should be determined in March, when two city-appointed commissions are expected to act on Patterson’s plans, but their authority apparently is limited to tweaking details such as setbacks or traffic patterns—a campground already is a permitted use in the rural residential district surrounding the pond. Meanwhile, the opposition is gearing up even more, despite the lack of a clear line of attack, with Dumont spearheading the creation of the Sand Pond Association “to protect, preserve and responsibly enjoy this little piece of heaven.”

Both sides, in other words, are pursuing their goals by appealing to a natural aesthetic that both also know no longer exists. “The wilderness” in this instance is little more than a muttered prayer, “Mother Nature” a saint whose help is invoked in battling a heathen foe—which is to say, the opposition.