One of the more insipid refrains the RV park and campground industry is prone to repeating is that it’s in the business of “creating memories.” These days, alas, those memories may start convincing a growing number of RVers that there has to be a better way to spend their vacation time.

The Memorial Day weekend was notable for tornados that essentially wiped out at least two RV parks, in Texas and Oklahoma, but at least three other campgrounds preceded them this year alone: Florida Caverns RV Resort, hammered in January; an RV park east of Madison, Indiana, blasted by an EF2 tornado in mid-March; and a campground at Hanging Rock in southern Ohio in early April that also got thumped. All sustained serious damage, but the violence this past weekend took matters to a whole new level.

At the Will Rogers Downs KOA in Claremore, northeast of Tulsa, an EF2 twister slammed into a campground that had 146 occupied sites, converting an Airstream trailer into a silver bullet that flew the length of a football field, flipping large motorcoaches and tearing apart travel trailers. That same Saturday, 220 miles to the south-southwest, an EF3 tornado made mincemeat out of the Lake Ray Roberts Marina and its 47-site RV park, just five years old, leaving a half-mile-long debris field. That no one was killed at either campground was simply a matter of luck: both twisters hit at night, with campers given no advance warning. And while the Oklahoma park has a storm shelter, not everyone managed to reach it in time.

May tends to be peak tornado season, with such storms declining in frequency through June and into July. But that doesn’t mean the danger they pose is entirely over—and as their threat diminishes, their big cousins are just stepping up to the plate. Hurricane season typically runs from June 1 to Nov. 30, and aside from being themselves a significant threat to coastal areas and as much as 200-300 miles inland as far north as Maine, hurricanes also can spawn tornadoes. Meanwhile, 2024 promises to be one of the most active hurricane seasons on record, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasting eight to 13 hurricanes, including four to seven “major” hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph or higher.

None of that sounds like picnicking weather, nor does the less dramatic but even more deadly cause of all that turbulence, a rapidly warming atmosphere above and oceans below. Heat-related deaths have been rising steadily since 2014, and the number of extreme heat days in some states is now five times higher than 40 years ago. So the American southwest, while relatively safe from tornados and hurricanes, actually kills far more people than either of those headliners simply by baking them to death. Phoenix last year had 54 days when temps hit 110 or more; Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, had 645 heat-related deaths in 2023.

(Pity poor Houston, which gets a triple whammy of hurricanes, tornadoes and excessive heat: this past weekend it broke all records by registering a heat index of 115 degrees. In May.)

Given the above extremes, it’s hard to think of a more inappropriate shelter in which to confront the elements than an RV. These boxes on wheels become ovens in a heartbeat if they lose power with which to run their air conditioners, and they’re far more vulnerable than most housing to the baseball-sized hail that’s seemingly ever more common throughout the South and Midwest. Staple-and-glue construction techniques used to assemble cheaper rigs, be they travel trailers or class Cs, guarantee they’ll crumple or fly apart under even a moderately vigorous shaking. And even the most solid fifth-wheels or motorcoaches present sail-like silhouettes to winds strong enough to flatten commercial buildings, never mind dwellings that have only four unanchored points of contact with the ground.

Yet despite these obvious and growing vulnerabilities, the RV industry does nothing to alert the public to the heightened risks it takes when camping in certain areas at certain times. Indeed, it has been positively euphoric when announcing in recent weeks that 45 million Americans “are gearing up for RV adventures this summer,” with an industry chief marketing officer crowing that RVing “offers a unique combination of freedom, adventure and value” and an opportunity to . . . wait for it . . . “create unforgettable memories.” Indeed. Matt and Anna Conners, quoted in numerous news stories, undoubtedly will long remember the night they had to pound on the doors of a storm shelter at the Will Rogers Downs KOA to escape the tornado that flipped their Coachmen Class A.

But it’s not just campers who are being led down the primrose path—so are campground owners, who tend to be blasé about the risks they face, dismissive of climate change warnings and oblivious to how quickly the overall weather outlook is deteriorating. The Lake Ray Roberts Marina RV park, which as mentioned above was opened a mere five years ago, lies just north of Denton, Texas, and right at the base of the area with the highest average number of tornadoes per year, as indicated on the map below. That apparently didn’t dissuade anyone from building the campground, and apparently wasn’t ominous enough to prompt the CYA construction of an underground storm shelter.

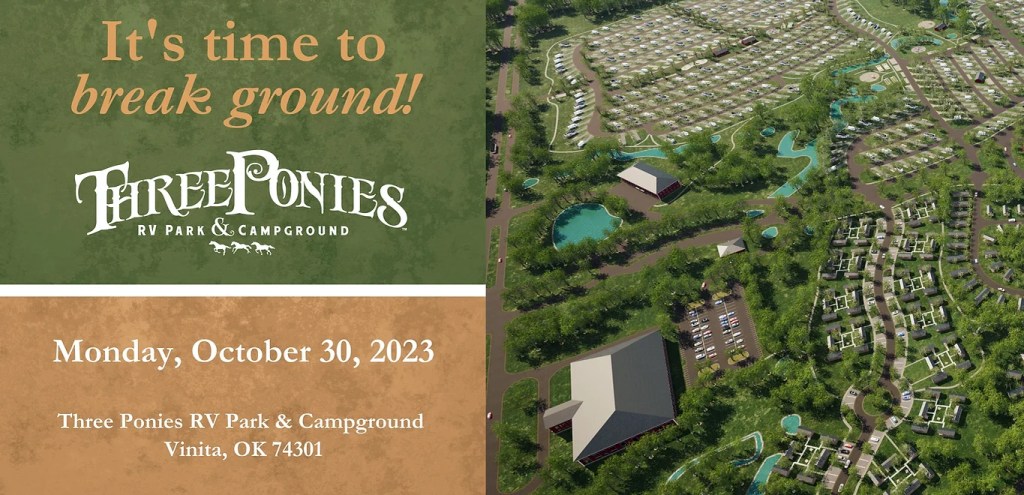

Meanwhile, as I wrote earlier this month, a similar indifference to facts on the ground has enabled ongoing planning for a $2 billion-plus amusement park and RV park with more than 1,000 sites and cabins in northwest Oklahoma—just at the edge of that deep maroon blob in the middle of the map. How different is that from building a tourist attraction on the lip of a dormant but not extinct volcano?

The problem is not that people with too much money and not enough sense are indulging in such follies, but that their willingness to do so creates a misleading sense of normalcy for other people who are just looking to have a good time—or even, heaven help us, who are hoping to “create memories.” Some significant portion of them will get more than they bargained for.