Given that many, many RV owners still think an electricity-powered RV is the stuff of science fiction, it’s perhaps surprising that a decidedly more outlandish concept was dropped into a panel on the subject last week without any comment.

The speaker was Ashis Bhattacharya, Winnebago Industries’ senior vice president for business development, strategy and advanced technology, so no slouch about technological development in the RVing world—even if he was off by a couple of decades. Speaking at an RV Industry Association webinar on the development of EV-RVs, Bhattacharya asserted Winnebago’s innovation chops by mentioning that the company had introduced a helicopter RV perhaps 25 years ago.

The comment apparently flew over everyone’s head. But if a first-tier manufacturer could add wings (okay, rotors) to the RVing concept, surely switching from a gas-driven technology to an electrified one can’t be too much of a stretch?

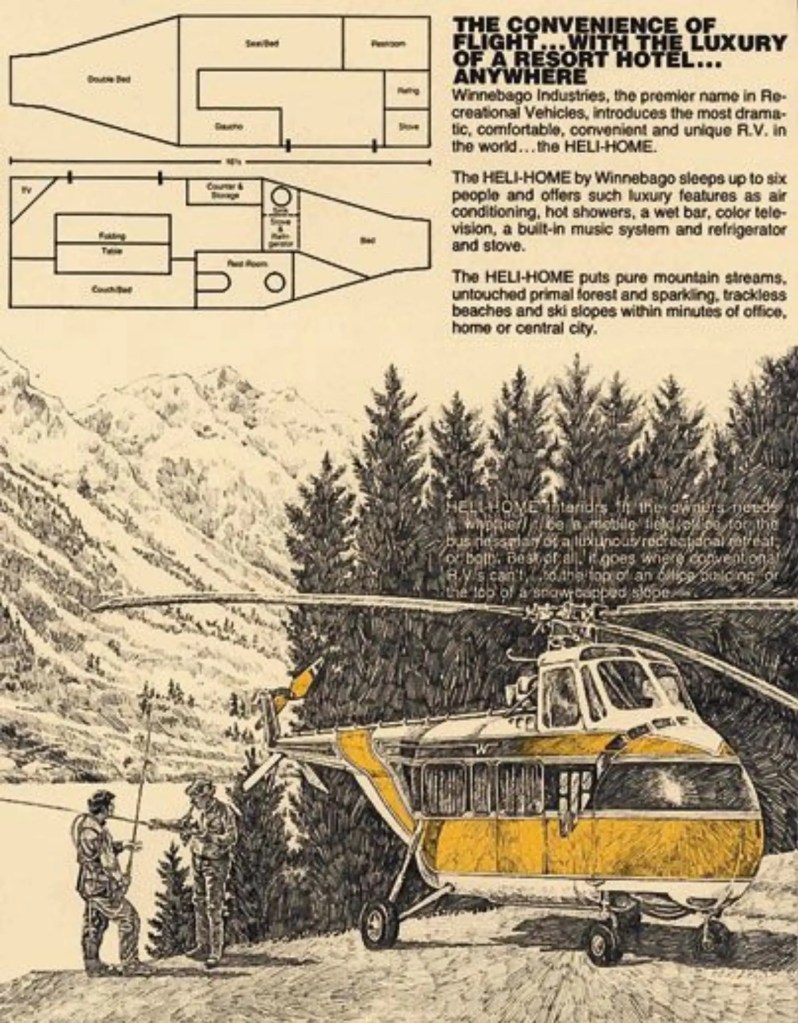

Not that Winnebago actually built its “Heli-Campers”—later changed to “Heli-Homes”— from the ground up, any more than it builds RVs from scratch today. But it did partner with Orlando Helicopter Airways, which in the early to mid 1970s was buying surplus military Sikorsky S-55s and S-58s for various civilian purposes. Half-a-dozen or so were furnished by Winnebago with a full galley with stove and refrigerator, twin water heaters, air conditioning and a furnace, a bathroom with holding tanks and shower, and sleeping arrangements (in the larger of two models) for six. Also included were a color TV and an eight-track tape deck (because, remember, the mid-’70s), a mini-bar, full carpeting and sound-proofing, a generator, an awning and, for a few extra dollars, pontoons for landing on water.

Heli-Camper performance numbers were more than competitive with today’s rolling homes: with a dry weight of 9,200 pounds, the flying Winnebagos could carry up to 3,000 pounds, had a cruising speed of 110 mph and a range of more than 300 miles. Plus, of course, the whirlybirds could access the most remote and trackless wilderness, outdoing even the gnarliest four-wheel drive RVs in search of boondocking heaven.

Only two stumbling blocks prevented the Heli-Camper from becoming a ubiquitous overhead annoyance in the backcountry. One was the price tag, which ranged from $185,000 for the base model up to $300,000—or between $1 million and $1.65 million in 2022 dollars. Even in a world of luxury Class As starting at more than half-a-million, that’s a lot of dollars.

Then there’s the little matter of knowing how to, you know—actually fly a helicopter. Winnebago tried to finesse that issue by creating a rental option for campers who wanted to hire a pilot, but even that was a pricey alternative, at $10,000 a week plus the pilot’s fees and cost of fuel. And then, of course, there was the whole sticky issue of what to do with that pilot once you reached your week-long retreat far from civilization. Perhaps it’s not surprising that neither sales nor rentals really took off, so to speak.

Still, if Winnebago was willing to take a shot at flying RVs, perhaps it’s only to be expected that today it would be at the forefront of the EV-RV ramp-up. At least with EVs the customer base is considerably larger, the cost per unit is a lot more within the public’s means, and there’s every reason to think that the technology will see constant improvement even as costs get driven down.

And then there’s this: those quiet and exhaust-less RVs will be a whole lot easier on the landscape than fleets of transport helicopters would have been, descending on whatever paradise you’d found. There’s good innovation, and then there’s the other kind.

Most recent posts