A staff writer and columnist for RVtravel, an online magazine and news service, yesterday demonstrated yet again why gypsies, travelers and other foot-loose wanderers so often are regarded with suspicion and resentment—not because of their supposed freedom, as some prefer to believe, but because they’re seen as parasites.

Writing under the somewhat misleading headline, “Full-time RVers not welcome here: South Dakota’s attempt to prevent RVers from voting and residency sparks outrage and concerns,” Nanci Dixon whined about a summons for jury duty received by her husband, requiring him to be on call for 30 days starting sometime in September. The problem? The Dixons aren’t actually in South Dakota, even though that’s where they get their mail, vote and have their RV registered. They are in fact full-time RVers and currently are working as campground hosts in another state, where they’re expected to remain until October 20. They also have medical appointments and a minor skin cancer treatment scheduled through that date. Jury duty over the next couple of months, as far as the Dixons are concerned, is simply a no-go.

Okay. Jury duty almost invariably is inconvenient—even for those, as Dixon claimed for herself in a subsequently appended comment, who “look at Jury Duty as a responsibility and an honor.” But when Dixon asked Minnehaha County officials to postpone this responsibility and honor, she was aghast at their response. “They showed no mercy,” she wrote. “We were only offered a chance to move it within the year. No, not next year after the spring thaw, but in November or December of this year. December in South Dakota in the winter . . . on icy roads . . . in a motorhome. And over Christmas! More than 1,600 miles from our snowbird retreat! To say I was shocked is an understatement.”

Wow. Inconvenience piled on inconvenience, by a court system that clearly doesn’t understand the Dixons aren’t, you know—South Dakotans. That the Dixons are horrified, for instance, by the idea of driving on their adopted state’s roads in winter, when apparently all of South Dakota should simply shut down. That the Dixons have pressing responsibilities, but apparently not in the state they claim as their own, with jobs in one place and a winter retreat in another and doctor appointments who knows where—except not, it seems, in South Dakota, so South Dakota’s people should just call the Dixons’ people and work out something that will fit the latter’s busy non-South Dakota schedule.

Again: wow.

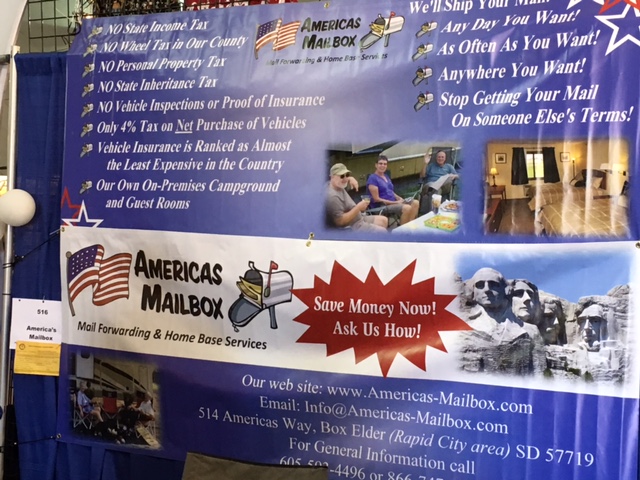

The irony is that this precious behavior is as much South Dakota’s doing as it is the Dixons’. RVers who have sold their bricks-and-sticks homes and live year-round in their RVs still need a legal address, so they can get mail and claim residency to open bank accounts, register to vote, apply for a driver’s license or perform any number of the other dull bureaucratic duties that come with living in a society. And South Dakota has been only too willing (as are Texas and Florida, to a slightly lesser extent) to court such low-maintenance customers, advertising itself as a low-tax, low-consequence haven for the foot-loose and fancy-free. No state income tax! No personal property tax! No pension or (state) social security tax! No vehicle inspections, low vehicle license fees and low, low car insurance rates!

Best of all, the whole “become a Mount Rushmore State resident” process is as slick as those icy roads Nanci Dixon doesn’t want to navigate in December. Spend a couple of hundred bucks for a mail box at one of a handful of mail forwarding services. Spend a night in the state to nail down your status as an “official resident.” (Indeed, one of those mail forwarding services, South Dakota Residency Center, operates out of the Spearfish Black Hills KOA campground—how convenient is that?) And just like that you’ll have everything you need to get a South Dakota driver’s license, good for five years before it has to be renewed, and the keys to the kingdom will be yours.

Almost.

One fly in this officially sanctioned ointment of fictional residency is that being domiciled entails having voting rights—and with a growing number of transient “South Dakotans” having no more connection to the state than a one-night stand, it’s fair to ask why they should have a voice in how the state or its counties should be run. As Dixon herself wrote, albeit to explain why nothing should be expected from her, “As most South Dakota full-time RVers, we rarely travel there. We do not use the roads, the schools, parks or a myriad of other things.” And yet as a South Dakota full-time RVer, Dixon can vote on tax issues, for South Dakota’s Congressional representation and for everything in between, including city council and school board positions. If the people who actually live in South Dakota decided, for example, that they should institute a personal property tax to help fund their public schools, any serious doubt about how the Rvers would vote?

Nor is this a trivial population. Americas Mailbox, one of the state’s biggest mail forwarding services, is located in the town of Box Elder and has more than 9,000 registered voters among the 15,500 people using its address. In the 2020 general election, according to reporting by local television station KELO, 5,856 of those “one-day residents” cast ballots—or more than half of the 10,119 people that actually live in Box Elder. Only 39 of those Americas Mailbox “residents” voted in person; the rest voted by mail.

Or consider a report by the Dakota Free Press that the “three residency mills” of Americas Mailbox, South Dakota Residency Center and Dakota Post have a combined total of 27,000 members. “If those ersatz residents all vote, they constitute 4.6% of the currently registered South Dakota electorate,” it summarized, observing that in 2018, Kristi Noem won her gubernatorial race by a margin of only 11,458 votes.

Such outsized influence by outsiders has raised some hackles in the state, which recently amended its voting registration laws to require that voters have “an actual fixed permanent dwelling, establishment, or any other abode” in South Dakota to which they return “after a period of absence.” The amendments also impose a new, 30-day period of actual residency before would-be voters can register, although it’s unclear whether the changes will apply to existing registered voters. The one-day requirement to establish residency, meanwhile, remains the same.

Yet as Nanci Dixon’s piece underscores, at least some full-timing RVers clearly want it both ways—something a preponderance of more than a hundred commenting readers pointed out—by having a minimum of responsibilities and costs while obtaining as many privileges and rights as any other member of society. By getting a free ride, or at least as close to one as possible. By paying low taxes, or none at all, while benefitting from roads, police and fire services and all the other trappings of civil society, not just in South Dakota but in all the other states in which they don’t pay the freight. By voting without living with the consequences.

By fussing over jury duty, for which there apparently is no convenient schedule.

For full-time RVers, all this is part of the freedom of the road they’ve chosen over the heavy chain of social obligation that weighs down everyone else. For many members of that “everyone else,” however, that marks the full-timers as freeloaders, the grasshoppers having their day in the sun while the ants toil away against the coming winter. Nice work if you can get it—but is it reasonable to pout when the ants require a little contribution to the public weal? Shouldn’t the inconvenience be met with grace, out of recognition of the blessings that have been bestowed?