Last summer I reported on a possible silver lining to the grey cloud of plunging RV sales: the decline in high-margin sales meant dealers had more incentive to beef up their servicing efforts. Complaints about months-long waits to get even basic repairs had been exploding, thanks in part to shoddy workmanship and substandard parts as manufacturers rushed product out the door—then dragged their heels on approving warranty repairs. Add a resulting shortage of replacement parts, and the completely predictable result was an average wait time last May of 34 days for non-warranty work—but 50 days for warranty repairs.

And if even one part was out of stock? That national average jumped to 73 days for non-warranty work, 89 days for warranty repairs.

Crazy, right? But that was actually an improvement over December 2022, when the national repair time had averaged 53 days, and the wait time for both warranty and out-of-stock repairs had nudged down a bit. Not a huge change overall, true, but moving in the right direction and with every reasonable expectation that the improvement would continue.

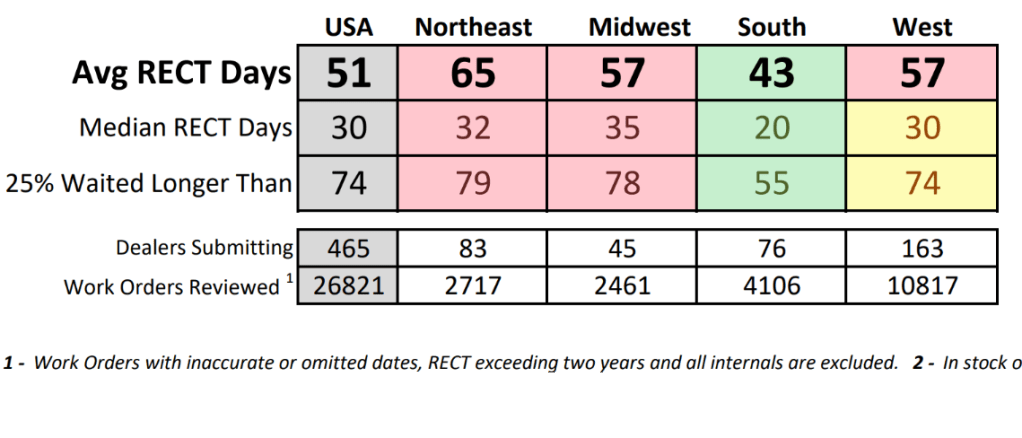

But that was then, and this is now. The average national repair time this past December shot back up, to 51 days—and if you’re unlucky enough to be in the northeast, that average was 65 days. In May, 25% of all customers had to wait longer than 33 days for their repairs to be completed; in December, that wait time for the unlucky 25% had more than doubled, to 74 days. The national average wait of 50 days for warranty repairs in May had jumped to 67 days in December, and to a whopping 90 days in the northeast. Meanwhile, the percentage of repairs that languished because parts were out of stock jumped to 33% in December from 21% in May, extending those repairs by another week.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. The number of RVs cranked out by manufacturers last year was roughly half that of 2022, which one might think would mean more time for quality control on production lines. Lower production and the repair of pandemic-disrupted supply lines should have replenished parts stocks, not squeezed them further. And after several years of pumping money into its technical institute, the RV Industry Association was boasting in December of having the largest number of certified techs in the RV industry’s history.

So where’s the bottleneck?

A good question, and one the industry hasn’t yet acknowledged, much less answered. To be sure, some of the numbers above may be attributable to seasonal variations, if inexplicably so: repair times seem to peak in December and January, then gradually decline through the spring and summer before bottoming out around October. Still, the latest peaks are significantly higher than those of a year ago, so progress this ain’t. The only thing certain is that RV owners who need repairs are still twisting in the wind, their expensive and frequently highly leveraged adult toys sitting on a dealer’s lot somewhere for months on end.

The data above, utilized by the RV Dealers Association for the benefit of its members, is extracted from much more extensive research conducted by a systems software company called Integrated Dealer Systems. Number nerds who would like to explore that information more thoroughly can go deeper here.