PMRV, for the uninitiated, means “park model recreational vehicles,” which is a nonsensical word salad. Consider, for example, that the La Plata County, Col. building code defines park model RVs as “a special subset of recreational vehicles that are constructed for the purpose of permanent placement in a park or a residential site.” (Why cite a Colorado county code to make a point? More on that in a moment.) The point here is that “vehicles,” defined as “things that transport goods or people,” ipso facto become non-vehicles as soon as they are in “permanent placement.”

Still, the obvious fiction that park models really are just RVs persists, thanks to vociferous industry lobbying. An interview in the current issue of Woodall’s Campground Magazine with Dick Grymonprez, who’s retiring as the longtime director of park model sales for Skyline Champion, has him triumphantly acknowledging that the RV Industry Association—on whose board he served for a decade—was in the forefront of rebuffing federal efforts to regulate park model designs and construction. “A few years ago, the Department of Housing and Urban Development was trying to say that park model RV manufacturers were advertising and selling the units as housing,” he recalled dismissively, without disputing the claim.

Park models were a cash-cow not easily relinquished, so it’s not surprising that the industry pushed back vigorously. But after defeating HUD’s efforts, it also did nothing to dispel the notion that park models are so much more than an RV. “I think a lot of people that buy park models are buying them for a second home or vacation home”—or more, Grymonprez added, with a “what are ya’ gonna do?” shrug of his metaphorical shoulders. “If you think about it, a person’s going to live wherever they want to live. The RV business doesn’t want to admit this, but there are people that live in RVs year-round, full-time. There are people that live in park models year-round.”

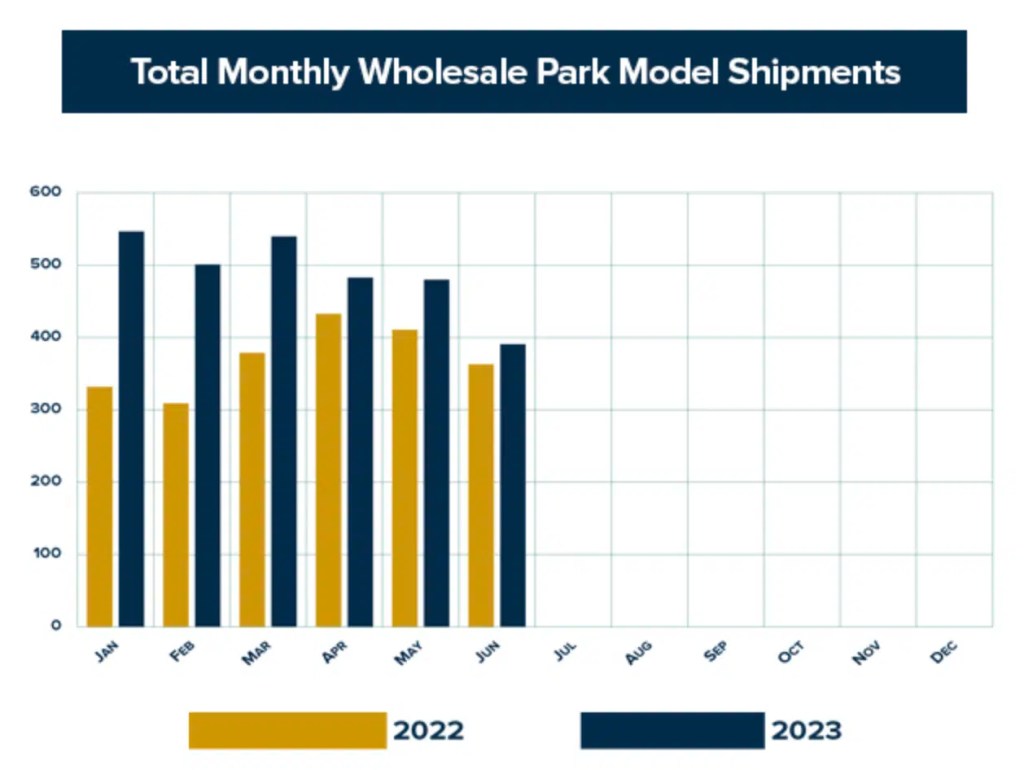

In some ways, this is old news; what’s more recent is the blasé attitude by industry leaders toward the possibility of serious challenges to the housing hybrid they’ve created. And why not? At a time when RV shipments across the board are plunging by 40% to 50% over year-earlier numbers, RV park models—as seen in the bar chart above—are the stunning exception. Month after month, park model shipments have strengthened over last year and are up 32.1% for the year through the end of June. And while total park model numbers are a fraction of overall RV shipments, they’re also significantly pricier pound-for-pound than their rolling counterparts and have seen the greatest price appreciation over the past few years.

(They’re also increasingly boxier. While limited to no more than 400 square feet [500 in Florida] by HUD standards, all but a handful of this year’s shipments have been more than 8.5 feet wide—the maximum width permitted for real RVs and tiny homes on wheeled chassis. Of the 2,942 park models shipped the first six months of this year, 2,921 were too wide to be wheeled down a highway without a special permit.)

Just how costly these putative “RVs” can become is suggested by an email I received last week from a reader who wants to build his own winter ski chalet at a resort in Colorado. In 2017 he purchased a 20′ by 102′ lot in a private gated campground for $19,000, with the thought of eventually putting a park model on the site. After grading and leveling, installing retaining walls, upgrading to 100-amp electrical service and installing a heated hydrant 12 feet deep, he figures his property value is now $135,000. But in the interim, park model prices increased so much that “what was 50k for a custom model is now in excess of 100k for a cookie-cutter standard model,” making him wonder whether it’s all worth it.

Spending upwards of $200,000 for 400 square feet on a sliver of land no wider than can fit a standard automobile cross-wise isn’t how I would spend that kind of money, assuming I had it to spend. Then again, I’m not a skier. On the other hand, this kind of housing development, disguised as a resort community, is becoming ever more common, and it makes its inroads by maintaining the fiction that 12- and 14-foot-wide park models are just RVs and therefore should be admitted wherever the rolling variety is allowed.

In La Plata County, as referenced at the top of this post and as I’ve written before, Scott Roberts, an Arizona-based developer, has advanced his plans to build the so-called Durango Village Camp on the banks of the Animas River. When first presented to local residents and planners last December, the proposal foresaw creation of a 306-site RV park that would include an initial 42 or maybe 49 park models, with more to be added in some indefinite future. According to Roberts’s business model, the park models would eventually be sold—perhaps for as much as $450,000, as they currently are at some of his other properties. Still, regardless of how much that may look like a housing development, Roberts argues that Durango Village Camp “most closely resembles an RV park,” and that’s one of the allowed uses on the property as currently zoned.

But that was then, and this is now. Earlier this month, the final Village Camp paperwork was filed with La Plata County—and in the intervening eight months the proposal’s make-up has changed considerably. Instead of the 306 sites Roberts initially proposed, Village Camp would have only 277—but of those, fewer than half would be RV sites. The balance would include 54 undefined “RV cabin sites” as well as 86 park models, or roughly double the initial number. The narrative laying all this out helpfully observes that the park models “are technically RVs, but their fit and finish is similar to an upscale hotel room with beds, a kitchenette, a bathroom and living room.”

Whether this would be an appropriate use for the property in question is best resolved by the people of Durango. But their job would be much simpler if the whole process were more honest and the evidence of our senses was accepted over industry word-play and obfuscation: a park model is no more a recreational vehicle than a mobile home is mobile. They’re both fixed dwellings, separated by an arbitrary dividing line based on square footage. Nor does it help that zoning regulations all over the country—not just in La Plata County—are years behind the times in recognizing changes in the definitions of camping, campgrounds, RV parks and, now, glamping.

Most recent posts