The organization formerly known as the National Association of RV Parks and Campgrounds, or ARVC, is having one heck of an identity crisis.

Last November, supposedly after a year of vaguely referenced “surveys and interviews,” the association’s leadership announced that it was “rebranding” itself and henceforth would be known as Outdoor Hospitality Industry, or OHI. That awkward word jumble without a subject noun was explained away by ARVC/OHI’s executive director, Paul Bambei, as marking the association’s transition toward becoming “the trusted voice of all outdoor hospitality.”

Delusions of grandeur, anyone?

While Bambei and his enablers thus laid claim to global aspirations for their modest little industry association, ARVC’s dues-paying members couldn’t help but notice that they had been disappeared. An organization originally founded “for the purpose of promoting camping through the private sector and protecting the camping industry from unfair legislation and unfair competition” apparently had decided that “camping” was—what? Too old-school? Too limiting? Just not as focus-group attractive as “outdoor hospitality”? Whatever the case, “campgrounds” and “RV parks” seemed to have ceased as an integral part of the organization’s identity.

Predictably, the grumbling soon started. Critics pointed out that the outdoor hospitality industry’s “trusted voice” presumably would be speaking on behalf of not just campgrounds, RV parks and glampgrounds but also bed-and-breakfasts, inns, ski lodges, marinas, resorts and even hotels and motels if they were in any way connected to the “outdoors.” Worse yet, the new “outdoor hospitality” umbrella would cover Harvest Hosts, Boondockers Welcome and Hipcamp, long seen by many campground owners as unfair competitors who don’t have to comply with RV park licensing requirements. How would all these disparate businesses have their conflicting interests represented by a single voice except in the most abstract sense?

Less than a month later, the grumbling became more serious when the Pennsylvania Campground Owners Association voted to quit its partnership with OHI. The national organization’s “mission and vision” no longer aligned with its own, PCOA leadership explained, adding that its members had grown increasingly concerned about OHI’s lack of communications and transparency about various changes it was implementing.

Decisive though it was, however, PCOA actually was slow on the uptake: ARVC/OHI had been signaling its intentions at least a year earlier, with little apparent pushback—and, indeed, may have been emboldened by the muted response. Early last year, for example, I wrote a three-part post making the case that ARVC had lost its way. (Indeed, in an ironic foreshadowing, I suggested at the end of the second installment that “perhaps it should rebrand as the National Association of the Outdoor Hospitality Industry.”) I observed at the time that ARVC had adopted a “mission statement” that was couched “in soulless corporate-speak,” to wit: “We empower outdoor hospitality businesses by providing industry-tailored resources, organic connections, consumer exposure, professional development, and proactive legislative action.”

This past week, apparently in belated response to PCOA’s secession, ARVC/OHI backpedaled furiously. According to its press release, because the new mission statement neglected to explicitly identify its “core membership,” the wording would be changed to the following: “To empower RV parks, campgrounds and glamping businesses with the community, resources, professional development, and legislative advocacy needed to ensure successful futures for all Outdoor Hospitality Industry businesses.” (The new wording, it added, is to be approved at ARVC/OHI’s board meeting this spring—raising the question of just who decided this is a good idea that should be announced before board approval.)

No mention of the name change to OHI and its silence on the subject of camping. No mention of OHI’s “vision” statement—“an empowered outdoor hospitality industry”—also cited by PCOA as a point of contention.

The proposed new mission statement is known as trying to have your cake and eat it, too. As with most such efforts, however, it fails as a semantic construct, since there is no logical connection between empowering RV parks, campgrounds and glamping businesses on the one hand, and ensuring the successful futures of all outdoor hospitality businesses on the other. The “empowering” of a part does not ensure the success of the whole. On the other hand, the way this sentence is constructed, its unmistakable meaning is that RV parks and campgrounds need to up their game so that the outdoor hospitality industry as a whole can thrive.

Bambei, meanwhile, proved himself just as fuzzy-minded as the organization he leads by insisting in the press release that the core constituency he serves really hasn’t changed, “it’s simply expanded.” Which is not unlike saying our little town of New Amsterdam really hasn’t changed, it’s simply expanded—into New York City.

But logical thinking and precise language aren’t the point: muddying the waters is. Whatever he may say after the fact about his primary concern for ARVC/OHI’s “core,” Bambei just can’t keep his grandiose ambitions from spilling into the open—and so, in that same press release, he goes on to to declare that “we know it is important that the hospitality industry has a national organization positioned to represent it well into the future.” And so, by golly, the RV park and campground industry might as well shoulder that burden on behalf of all those other unrepresented businesses. With Bambei at its helm, of course.

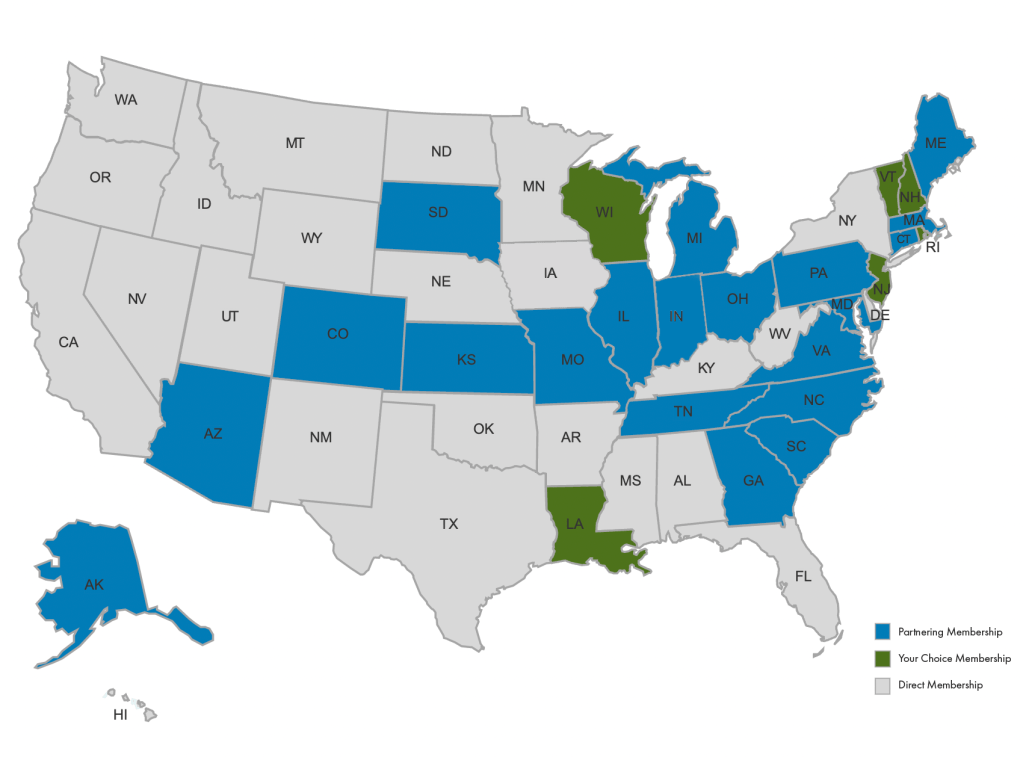

PCOA’s secession apparently had another, more salutary effect: almost simultaneously with its announced mission restatement, OHI’s board voted to allow direct RV park and campground membership across the United States. In doing so, it ended a much-criticized requirement that campgrounds in partnering states—like Pennsylvania—could belong to ARVC only if they first joined the state organization. (On the flip side, campgrounds that belonged to a partnering state association were in most cases required to pay national dues even if they didn’t want to be ARVC members.) That compulsory package deal was so unpopular that the country’s biggest state associations had been seceding from ARVC, one by one, with Pennsylvania’s departure the final straw.

But while long overdue, this change means that OHI will relinquish having captive dues-payers delivered by compliant state associations and will have to actually earn those members by convincing them it has their best interests at heart—a daunting prospect for an organization increasingly criticized for being out of touch with its grassroots and given to top-down decision-making. That, as much as any dreams of representing a vaguely defined but overarching “hospitality industry,” explains why ARVC/OHI seems so unmoored these days.