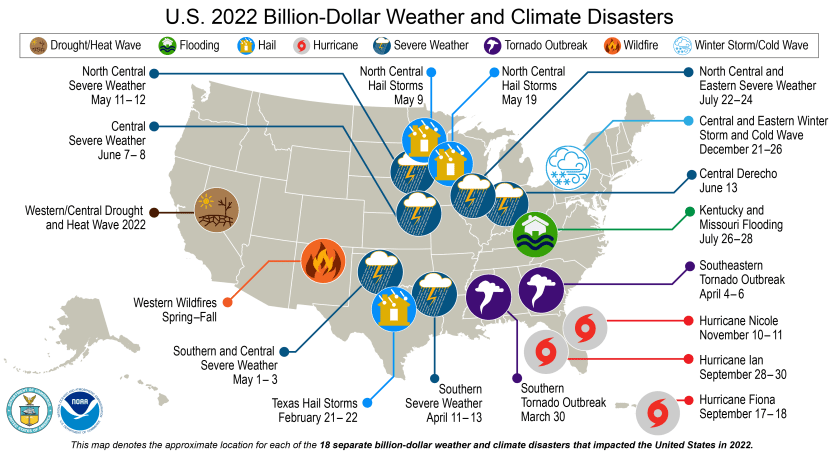

California is burning once again, after a two-year hiatus, with something like 200,000 acres already turned to charcoal—and here it is only mid-July, with three to four months of fire season still ahead of us. The state’s property insurance premiums are getting hiked by 30% or more a year. Wildfire smoke, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) analysis released in April, is contributing to nearly 16,000 deaths annually across the U.S. as a consequence of large wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada.

Alarming, right? The kind of apocalyptic onslaught that would have any thoughtful outdoor industry leadership publicly fretting about a proper response—but hey, this is California, long renowned for living in an alternative reality. So when Dyana Kelly, president and chief executive of the California Outdoor Hospitality Association, recently took figurative pen to paper to address the burning (sorry) issue of the day, it was to go after . . . the organization formerly known as the National Association of RV Parks and Campgrounds (ARVC). And not for anything having to do with weather, wildfires, insurance rates or other existential threats to the RVing lifestyle, either.

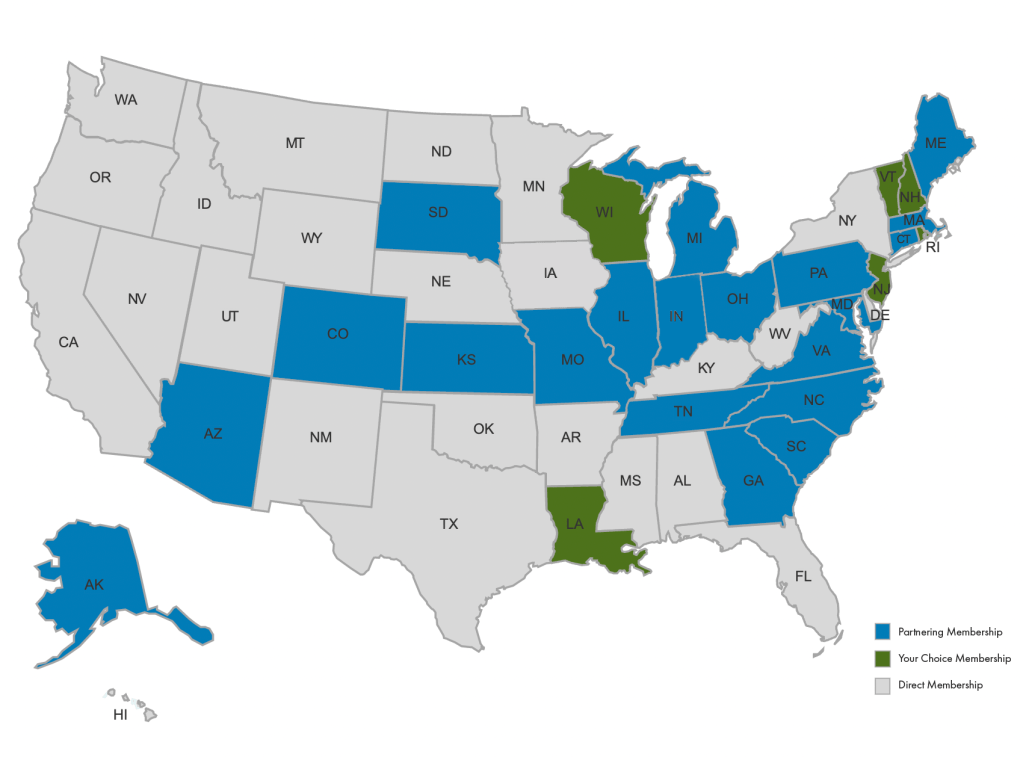

No, what ruffled Kelly’s feathers was ARVC’s temerity in rebranding itself as OHI, or Outdoor Industry Hospitality, which aside from being an awkward three-legged stool of a name is strikingly similar to CalOHA, which is how Kelly’s organization usually styles itself. The rebranding is not news—it happened early this year—but Kelly greeted it as though it were, sarcastically congratulating ARVC for moving “away from the standard membership of RV parks and campgrounds by partnering with Hipcamp and allowing non-permitted parks, dispersed campgrounds and possibly even backpacking locations (as indicated by their release video) into membership.” Ouch.

This kind of frontal assault in an industry of glad-handers and back-slappers was notable enough for RV Business to seek Kelly’s permission to reprint her broadside, originally written for CalOHA’s members. But to be fair, Kelly was only playing tit for tat: it wasn’t all that long ago that ARVC took legal action against the California association after it dropped its affiliation with the national group but retained the CalARVC name. The similarity, ARVC contended, was causing “confusion” for park members. So rather than get embroiled in a trademark tussle, the Californians switched to CalOHA—only to now find their roles reversed.

“Is there confusion,” Kelly wrote, reprising ARVC’s earlier complaint. “YES. A number of parks have called to inquire about an invoice they received recently from ‘CalOHA’ when it was actually a well-disguised invoice from OHI.”

Yes, of course this is a problem—but not, I’ll submit, as big as the problem that both CalOHA and OHI are resolutely ignoring. Bookkeeping confusion pales beside the fundamental climate threat to RVing’s business model, which if nothing changes will make the current contretemps seem more than just a bit precious. And quite irrelevant. But both organizations are carrying on as though it’s business as usual—nothing to see here!

If Kelly wanted a truly righteous fight to pick on a national stage, she’d take ARVC/OHI to task for its history of climate change denial. This is an organization whose official policy maintains that there is still “considerable uncertainty surrounding the theories on climate change,” so much so that the only responsible thing to do is “more research, data collection and scientific analysis” before changing emission standards—or, indeed, doing anything at all that might have an economic impact on the industry. Of course, that economic impact is felt more severely with each passing year precisely because of such a don’t-rock-the-boat approach.

Yes, that would be a righteous rumble, but also a hard slog. And not nearly as satisfying as a quick and dirty couple of jabs over something as relatively meaningless as what we choose to call ourselves.